Although I have been baking for over fifty years, it is only over the past decade that I have been writing about bread. I would pinpoint my inspiration, in bakers terms my “chef”, as being The Handmade Loaf, the seminal baking book by Dan Lepard. As sourdough bakers know all too well, it does not matter how good your starter is, what matters is your love for it, your ability to nurture and feed it, to add complexity: “saveur” and “provenance” so that it ultimately becomes a reflection of your bread making process, your life.

Over the past two decades, Dan has gently but doggedly nudged me to “bake” my book. “It is no use having a starter unless you actually make a loaf of bread” he would say to me. I have written slices of life from some of the most inspiring and insightful bakers, seed savers and farmers from around the world.

A Lammas prayer:

“From the fields, through the stones

Into the fire. Earthly bread.

As the wheel turns

May all be fed”

Remembering that before the monotonous grids of plant prisons, wheat used to represent the cycle of the seasons, the circle of life and death. Our ancestors carried this knowledge inside them like seeds that carried the codified magnificence of the plant. To rediscover the ancient wisdom we need to look into the wisdom of the seeds; our heritage is bound inextricably with the cereal that has nurtured us for over ten thousand years. But our original wheat has been domesticated, killed, like John Barleycorn, through overfarming on overworked land by over-settled people.

To find our “seeds” and recreate beautiful farming we have to be quiet and be at home on the earth; then there will be a flowering of wisdom. The new seed savers are like the ancient priestly farmers, they are re-discovering sacred re-hybridisation, rather than following the path of scientific hybridisation. The ancient Turkic and Scythian tribes used to plant the living seeds of the deceased on top of their burial mound (Kurgan). It was not a symbol of the power and wealth of the deceased, that was buried inside the tomb, but more an offering to the next generation, who could visit their ancestors' graves to refill their seed jar. It was in effect a living seed bank.

I believe that my ancestors also had a similar relationship with the land and their seeds, but Christianisation and industrialisation smashed their ancient seed jar and destroyed the fabric of community that had taken generations to weave.

Over the past decade I have researched and written about the culture of bread viewed through the working lives of modern artisan bakers. Through their stories I aim to shine a light on the following topics:

Why modern bread is bad for you

Small is beautiful, Seed sovereignty versus seed hegemony

History and evolution of wheat in the fertile crescent

Pagan Myths, Folklore and Traditions of Wheat and Bread

Current efforts and challenges to re-introduce heritage/healthy wheat

Peak soil

Baking as a “lifestyle” profession

Bread poverty and the role of the Multinational seed corporations

Two tier food system. Exclusive artisan bread v ubiquitous cheap bread.

Re-emergence of artisanship

What is authenticity?

I am greatly inspired by a poem by Daniel Varoujan “To the muse”. It comes from his book The Song of Bread. It is my muse, guiding me in my writing, to find the stories, the songs that speak to the world. Her inspiration will guide me as I seek to inform and elucidate the history of bread and how to save it for future generations.

To the muse. Daniel Varoujan

Teach me, oh muse of my sires, teach me.

How the lean labourer grips and guides

The curved handle of his plough as it parts the soil

How beneath the glowing rays

The barren furrows become fecund

How on the threshing floor the golden grain

Grows higher as the mill stones groan

How the rising dough slips easily from the wood

As the peasant feeds the full fired oven.

What happiness, what cosmic creation

This bread, this sacred bread giveth.

Teach me all this, the muse of my ancestors.

Guide me, garland my lyre with sheaves of wheat

As resting by the mill, neath shady willow

All my songs are born

I discovered this poem whilst hitchhiking to Yerevan three years ago in search of Armenian bread traditions. I got a lift with a local who spoke a little English, he told me about Varoujan. Unfortunately I could not find "The Song of the Bread" in Yerevan but I discovered a translation from 1940 and with the help of an Armenian friend I have translated it into English.

The book is Varoujan’s attempt to portray in poetic form the magnificence of bread, from field to table

The earth

The ox

The seed

The sun

The rain

The mill

The wild yeast

The hearth

Man takes these notes and creates the song of life - bread. Earth is not man's dominion but his muse. Man knows that only by respecting and honouring what gives him life will the song continue to be sung.

Man’s covenantal relationship with bread

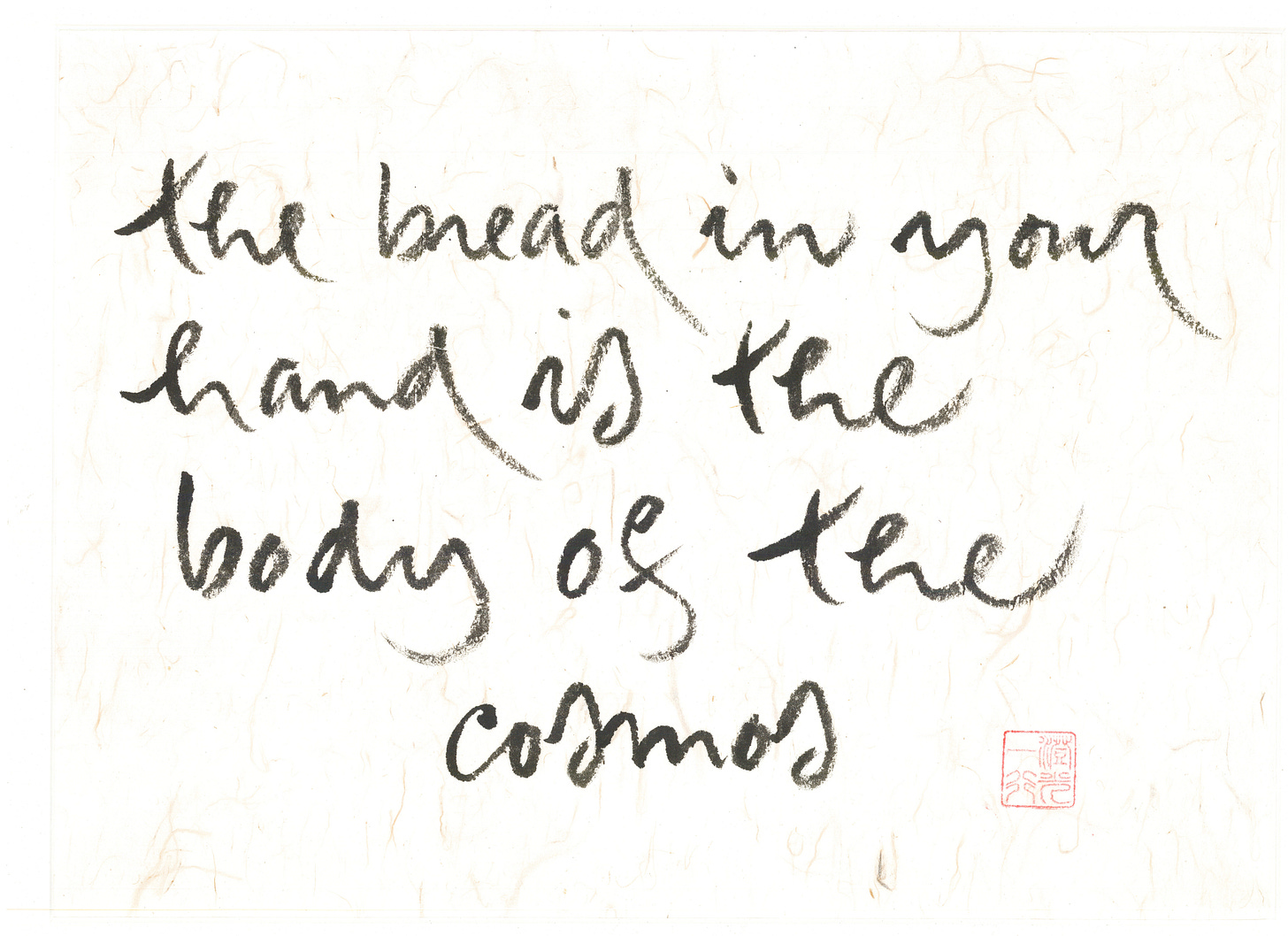

For several millennia there was a sacred relationship between humanity and the cosmos.

As Zeno of Citium, the founder of Stoicism, wrote in the Third century BC

“All things are parts of one single system, which is called Nature; the individual life is good when it is in harmony with Nature.”

This sympathetic magic and belief ensured we had sufficient food to survive. I believe the erosion of our divine connection to Mother Earth has ultimately led us to today’s disastrous farming system that is destroying our planet. This agri-cultural pogrom began in the 18 century with the exodus of land workers to the mills and factories in Northern Europe, enforced mechanisation and the subsequent loss of craft skills. The corralling of rural workers into cities destroyed several millennia of farming culture that had nurtured “seeds of wisdom”. From these seeds there grew rituals, songs, language and stories, and tribal ancestral memories flowered. Ethno-anthropologists talk of the ancient seed jar, in Mayan culture it is known as the Ruk’ux- or soul of a village. Keeping the seed heart of an abandoned village alive is an impossible task, it cannot be thought into reality, it has to be done through physical work- planting, harvesting whilst singing and praying. Just like seeds cast on to stony ground wither and die, ancestral songs go unheard inside the raucous noise of the factory.

There has always been a special sacramental relationship between bread and humans. This evolved over the 10,000 years since humans began to farm and create communities; in effect, wheat created civilisation, hence the importance of bread in all three monotheistic religions. This sacramental relationship has been weakened by urbanisation, for although this initially led to greater religiosity, the long term secularisation of society and the invention of the Chorleywood Bread Making process in 1961, which allowed for the industrial production of bread from industrially grown wheat, has rendered our current relationship with bread as simply carbohydratatory (sic). After 200 years of industrial revolution and 50 years of industrial agriculture the covenant has been broken; we have sterile soil and seed hegemony. Humans have evolved to the point where we are eating unholy bread that is destroying us and growing unhealthy wheat that is destroying the earth. If we restore the sacramental relationship by eating good honest bread, then we can begin the process of restoring the sacred relationship between humans and the earth.

The Japanese farmer poet Masanobu Fukuoka understood this. In his seminal book, The One Straw Revolution, he wrote

“The ultimate goal of farming is not the growing of crops but the cultivation and perfection of human beings”

To paraphrase Fukuoka

“The ultimate aim of the baker is not the baking of bread, but the bringing together of people and the nourishing of relationships”

Baking flat breads in the mountains of Kurdistan

Our sacred relationship with the soil was destroyed by the invention of industrial ammonium fertiliser by Fritz Haber and Carl Bosch in 1910. They invented a way to extract nitrogen from the air and from it they synthesized fertilizer, previously it had only been available from the earth; now bread could be conjured from fresh air.

The sacred bonds were finally rent asunder by the pioneering work of Norman Borlaug at the Rockefeller wheat breeding research centre in Mexico. In 1953 through scientific hybridisation he created the first dwarf spring wheat, a “plant” that was totally reliant on man made fertilizer. This was the beginning of the so-called Green Revolution; Borlaug received the Nobel prize for his work, and many people credit him with saving millions of people from starvation. But modern historians have begun to question the efficacy of the Green Revolution. It set in train a sequence of events that has led to the disastrous farming system controlled by what Vandana Shiva has termed “The Poison Cartel”, a group of 6 enormous multinational seed, chemical and agri-corporations. Although there is no doubt that increased yields afforded by modern industrial agriculture have fed a rapidly expanding global population, the costs in terms of human health, global health and soil health are becoming increasingly onerous. This crisis was brought to the world’s attention by David Montgomery in 2008, he coined the term, Peak soil, but it took several years before the soil crisis became headline news. The Head of the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organisation recently reported that a third of the world’s soil has already been degraded. In his 2018 book Robert Biel wrote ”The loss of soil is one of the profoundest features of what we can see now as a crisis, not just of food systems, but of humanity’s relations with nature”

As Wendell Berry wrote,

“When we change the way we grow our food, we change our food, we change society, and we change our values”

I have written stories of bakers who are planting seeds in their communities. They are in their own way attempting to re-sacralize bread by recreating connections in fractured communities and passing on craft knowledge to the next generation. They are not only healing those poisoned by modern bread, they are also helping farmers to heal the earth. They are not doing this out of religious conviction, each of them has a calling to bake, a personal relationship with their bread. The web of links between artisan bakers are many, the bonds strong. Like an intricate gluten structure they support each other with advice, help, recipes, labour and even equipment. Individually they have taken their starter and created their own Bethlehem or house of bread. Together they have created a renaissance in bread culture. More than ever before people are recognising the importance of good bread to our health, our society and our environment. Each one of these bakers has their own story which highlights one particular facet of this broader picture.

Baking bread at The Somme, WW2 rememberance event

Although their recipes contain the same basic ingredients of flour, water and salt, each baker has taken their “chef” fed it and nurtured their own starter, and then created their own bread story. What these bakers all have in common is selling their bread story every day of the week, to customers who acknowledge that story and buy into it, and bite into it.

So from one “chef”, I have found many starters and many bakers. If you are interested in reading more of my stories then please subscribe. Currently you can read without payment, maybe in time I will introduce a paid subscription. If you have enjoyed this then I would really appreciate it if you could visit my crowdfunding page here Crowd funding campaign and make a small donation or pledge. There are several rewards. I am raising money to renovate an old bakehouse in my house in Georgia to create a place of baking excellence where the traditions I learnt over fifty years ago can be preserved.

Here is a short video of the bakehouse I am renovating Swallows nest bakehouse renovation